McCormick Place, Lakeside Center

Sunday, September 25, 2005

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

McCormick Place, Lakeside Center

Monday, September 26, 2005

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

McCormick Place, Lakeside Center

Tuesday, September 27, 2005

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

McCormick Place, Lakeside Center

Wednesday, September 28, 2005

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

8011

Facial Cutaneous Anthrax, Prompt Recogition Required for Accurate Disease Surveillance

Accurate diagnosis of cutaneous anthrax, appropriate management and prompt disease surveillance depends on clinicians been familiar with the characteristic appearance of typical skin lesions. This has become more imperative with the emerging threat of bioterrorism worldwide. Plastic surgeons may well be initially consulted if a patient develops a cutaneous anthrax lesion in a non-endemic environment. Anthrax is primarily a zoonotic disease (e.g. cattle, goats and sheep) .1 However cutaneous anthrax is seen in patients who are exposed to contaminated meat or animal products in endemic countries such as Haiti. If affected patients receive prompt antibiotic therapy, their mortality rate is significantly reduced (25% to <1%) .2 Inhalational and gastrointestinal anthrax resulting from respiratory exposure or ingestion of anthrax spores respectively are less common (10% of naturally-acquired anthrax) and have a worse prognosis even with appropriate therapy.

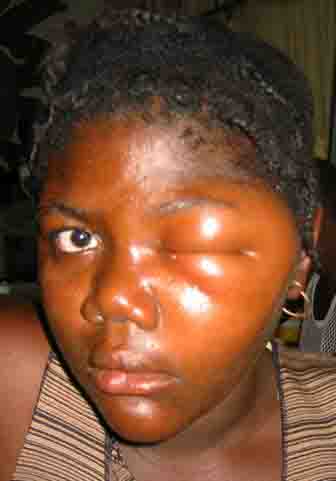

The evolution of a characteristic facial lesion of cutaneous anthrax is outlined in a seventeen-year-old girl (Figs 1, 2 & 3) who was treated at Hôpital Albert Schweitzer in Deschappelle, Haiti. She lives in a remote region of the Artibonite valley where anthrax is endemic. She was apparently exposed during the slaughtering process of a presumably infected cow. Her mother had a similar facial lesion (Fig. 4), which highlights the importance of seeking out other individuals similarly exposed.

The facial lesions of cutaneous anthrax occur predominantly in the cheek region, presumably through the contamination of abraded skin during the process of patients wiping their faces. The notable soft tissue swelling (Fig. 1) resulting from an edema toxin

(pX01) is characteristic for facial cutaneous anthrax, especially when associated with the typical evolution of this skin lesion. The initial papule evolves to a vesicular stage often with associated satellite vesicles (Fig. 2). Typically these vesicles form an ulcer over a period of 7-10 days with a depressed central black eschar (Fig. 3). Bacillus anthracis, a gram positive, non-motile, spore forming “box-car” like bacillus can be identified by gram stain and culture from fluid obtained from these vesicular lesions. 3 The appearance of these two patients' facial lesions is characteristic for cutaneous anthrax. Recognition of this pathogonomic lesion allows clinicians to make the correct “spot diagnosis”. Management of naturally acquired facial cutaneous anthrax should include intravenous antibiotics therapy (penicillin G, 2MIU q4hrly or chloramphenicol, 1g q8 hrly) and supportive measures. The CDC recommends using fluoroquinolone therapy in a non-endemic environment (ciprofloxacin 500mg Q12 hrly) because of concerns for bioengineered resistant strains of B. anthracis. 4 Early tracheotomy may reduce the mortality in patients with progressive edema leading to airway obstruction. After the acute infection has resolved, the black eschar may be debrided and may subsequently require skin grafting. The mortality of anthrax may be reduced through prompt recognition of these cutaneous lesions and appropriate therapy. In non-endemic areas, cutaneous anthrax should now be considered in the differential diagnose of any suspicious lesions as they may represent the first sign of an impending terrorist attack. Astute clinicians should be suspicious, test for B. anthracis and report their findings to the appropriate public health service. 5 <>REFERENCES

- Cieslak, T. J. and Eitzen, E. M. Clinical and Epidemiologic Principles of Anthrax. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 5: 552, 1999.

- Bell, D. M., Kozarsky, P. E., and Stephens DS Clinical Issues in the Prophylaxis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Anthrax. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8: 222, 2002

3. Inglesby, T. V., Henderson, D. A., and Tonat, K. Anthrax as a Biological Weapon. JAMA. 281: 1735, 1999.

- Update: Investigation of Anthrax Associated with Intentional Exposure and Interim Public Health Guidelines. MMWR. 50, 2001.

5. Huges, J. M., Gerberding, J. L. Anthrax Bioterrorism: Lessons and Future Directions. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8: 1013, 2002.

View Synopsis (.doc format, 118.0 kb)