Tuesday, November 4, 2008

14392

Soft Polypropylene Mesh, But Not Cadaveric Dermis, Significantly Improves Outcomes in Massive Midline Hernia Repairs Using the Components Separation Technique

Purpose

The use of acellular cadaveric dermis for reconstruction of abdominal wall defects has gained popularity over the past several years, especially for procedures in a contaminated field. Though cadaveric dermis promotes tissue ingrowth and neovascularization, recent literature, in conjunction with our experience, has led us to question the long-term tensile strength and durability of cadaveric dermis in abdominal reconstruction. We limited our internal database review to all consecutive patients who underwent a modified components separation procedure by a single surgeon using either an acellular cadaveric dermis or soft polypropylene mesh underlay for closure of a midline ventral hernia defect. Our goal is to determine the overall procedure success and complication rates of cadaveric dermis versus soft polypropylene mesh underlay in abdominal wall reconstruction.

Methods

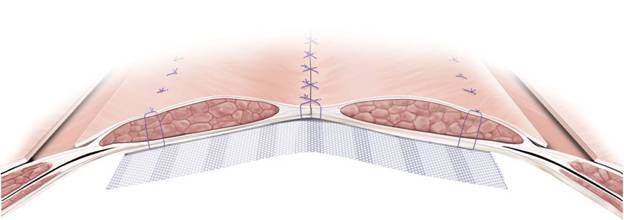

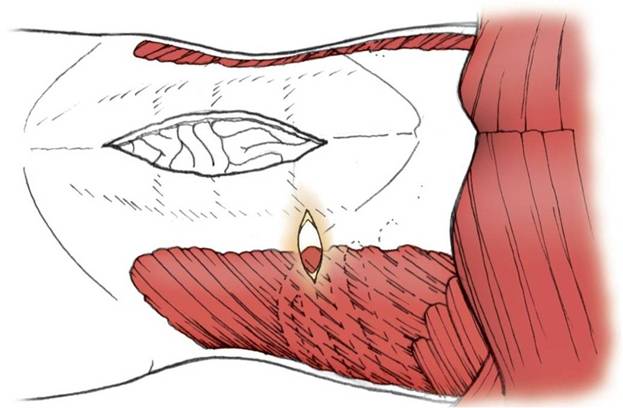

Between September 2004 and September 2007, 47 patients had a components separation technique where either acellular cadaveric dermis (n=19) or soft polypropylene mesh (n=21) was used as an underlay for fascial reinforcement but never as a “bridging material” at the time of primary or subsequent repairs (Figure 1). Additional patients (n=7) had cadaveric dermis placed during one procedure, followed by soft polypropylene in a subsequent surgery for the treatment of recurrence. In order to preserve periumbilical perforators and skin blood flow, the external oblique releases were performed through bilateral 6-cm transverse incisions that were made just inferior to the lowest aspect of the rib cage (Figure 2).

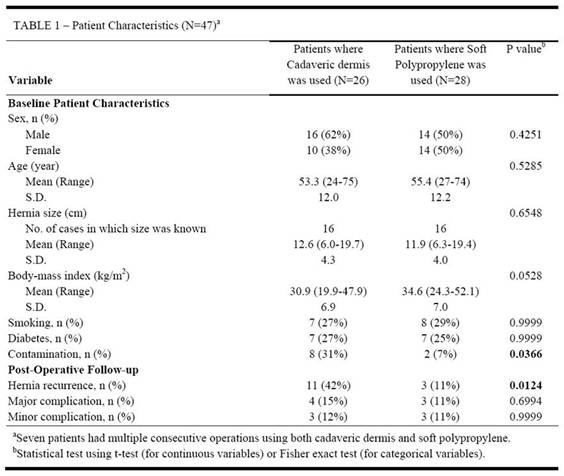

Results

The cadaveric dermis and soft polypropylene groups were similar in terms of patient demographics (Table 1), the main difference being the presence of contamination at the time of surgery—31% for the cadaveric dermis group compared to only 7% for soft polypropylene (p=0.0366). The use of acellular cadaveric dermis was associated with a 42% “true” recurrence rate that required re-operation, whereas soft polypropylene mesh had a significantly lower recurrence rate of 11% (p=0.0124). In patients where cadaveric dermis was used, the major complication rate was 15% with a minor complication rate of 12%, while soft polypropylene mesh was associated with a slightly lower rate of 11% for both major and minor complications. In terms of minor complications seen in both groups, cadaveric dermis demonstrated an increased incidence of post-operative cellulitis (11.1% compared to 3.3%). Two patients in the cadaveric dermis group required operative re-exploration for bowel obstructions, one of which was secondary to an incarcerated recurrent hernia. No patients in the soft polypropylene group have developed a bowel obstruction due to adhesive disease; however, one patient in the soft polypropylene group underwent a surgical revision at an outside hospital for undetermined reasons.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that soft polypropylene mesh exhibits markedly improved recurrence rates compared to acellular cadaveric dermis when used as a fascial underlay during components separation for abdominal wall reconstruction. Although the difference in recurrence rates may be partly due to the increased presence of contamination at the time of cadaveric dermis implantation, the long-term strength of the midline hernia repair, regardless of contamination, was not augmented by cadaveric dermis. The long-term strength and durability of intraabdominal soft polypropylene mesh are superior to those seen with acellular cadaveric dermis, and to this point, late mesh infections, fistulas, and bowel adhesions have not been observed in the soft polypropylene group.

See more of General Reconstruction

Back to 2008am Complete Scientific Program