Thursday, January 31, 2008 - 3:15 PM

13729

A Brief History of Plastic Surgery

Plastic surgery in modern times is a highly specialized field in which advanced technology and sophisticated techniques dominate. Today, the established goals of plastic surgery are to both restore normal form to disfigured tissues and to promote the enhancement of form. Hundreds of thousands of people benefit each year from the techniques that have been developed by plastic surgeons. However, as in all fields of surgery, the procedures that are common today were developed from the successive achievements of “giants” in surgical history. Since ancient times, a constant pursuit of knowledge has forged the art of plastic surgery into its present form. In 600 BC, the great Indian surgeon Sushruta described facial reconstructions using techniques ranging from pedicle flaps to free autogenous skin grafts (Figure 1). Sushruta is considered by many to be the “Father of Plastic Surgery”. He is best known for his technique of rhinoplasty to reconstruct noses that were mutilated as a penalty for crimes.

Gasparo Tagliacozzi is considered by many to be the first modern plastic surgeon (Figure 2). He performed reconstructions in patients mutilated in dueling, street fights or by diseases such as syphilis. His innovations included the distant pedicle flap, and the “Italian method” for the delayed arm flap. He also published De curtorum chirurgia, where he described and illustrated the instruments and techniques used in several different reconstructive procedures (Figure 3). It is considered by many to be the most important book in plastic surgery history.

Another important figure in plastic surgery history is Karl Ferdinand Von Graefe, a German military surgeon (Figure 4). His technical contributions consisted of advancements in blepharoplasty, palatoplasty and rhinoplasty. In 1818, he published his major work, Rhinoplastik, and became famous throughout Europe. And for the first time in reconstructive surgery history, the term “plastic” was used to describe a procedure.

Although initially, the field struggled with unfavorable perceptions, the war casualties drove the evolution and popularity of plastic surgery. Wounded soldiers would return home with extensive skull wounds, jaw fractures and facial burns. These horrifying wounds made it difficult to reintegrate back into society, as they were often met with disgust. The best medical talent from multiple nations devoted themselves to develop innovative reconstructive procedures to help their countrymen during and after World Wars I and II. One of the premier plastic surgeons during the early twentieth century was John Davis. He published the first American plastic surgery text, Plastic Surgery - Its Principles and Practice. Later he established the first plastic surgery fellowship program in the US at John Hopkins University. Finally, in 1946, Aufricht created the Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, which consolidated the presence of plastic surgery in the medical community (Figure 5). For the first time in American history, Plastic Surgery had become a defined field with its own board certification, journal, professional association and educational foundation.

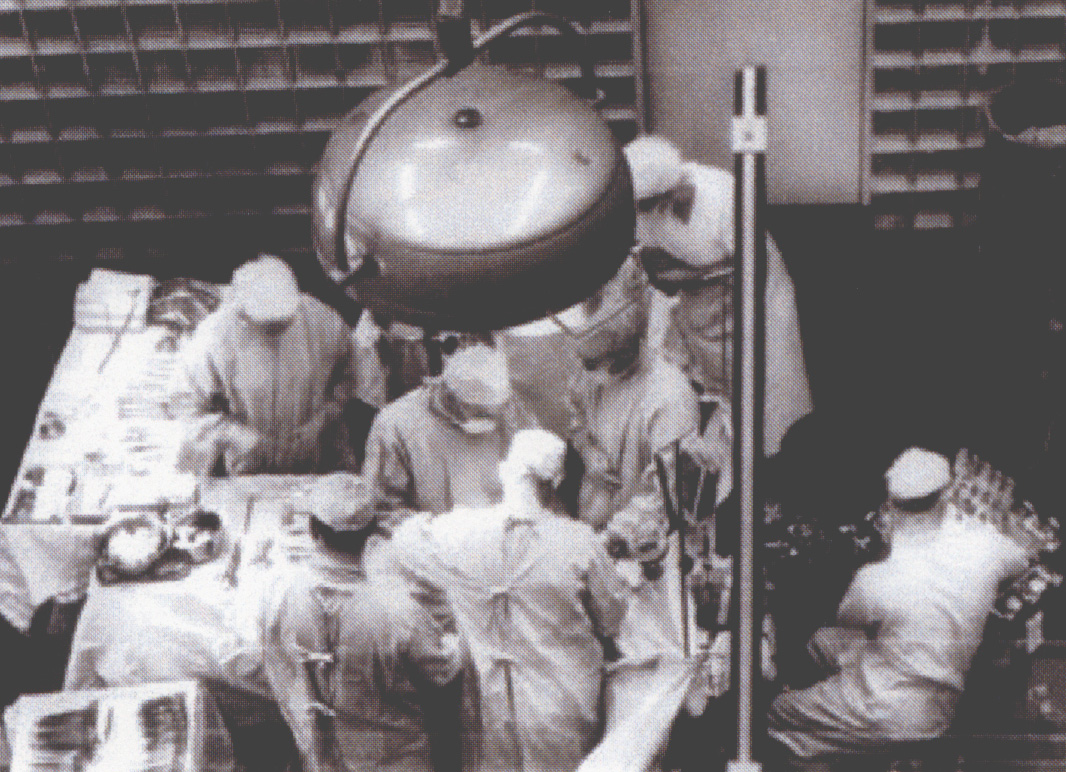

Recent leaders in the field of plastic surgery include, Dr. Hal Jennings (Figure 6), the first plastic surgeon to be appointed Surgeon General of the US and Dr. Joseph Murray (Figures 7, 8), the first plastic surgeon to be a Nobel Laureate. During the past few decades the field of plastic surgery has undergone numerous advancements and refinements. Procedures such as abdominoplasty, blepharoplasty, mammoplasty, buttock augmentation, mastopexy, lip augmentation, rhinoplasty, otoplasty, rhytidectomy, lipectomy and chin or cheek augmentation are now routine. Cosmetic procedures such as chemical peels, laser resurfacing, dermabrasion, and injections of Botox, Restylane, collagen, fat, and man-made fillers are also commonplace today. These innovations have helped a once denigrated field to become a modern subspecialty, from which hundreds of thousands of people benefit each year.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8