Sunday, October 10, 2004

6081

Recalcitrant Infection of Free Muscle Flaps by Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia

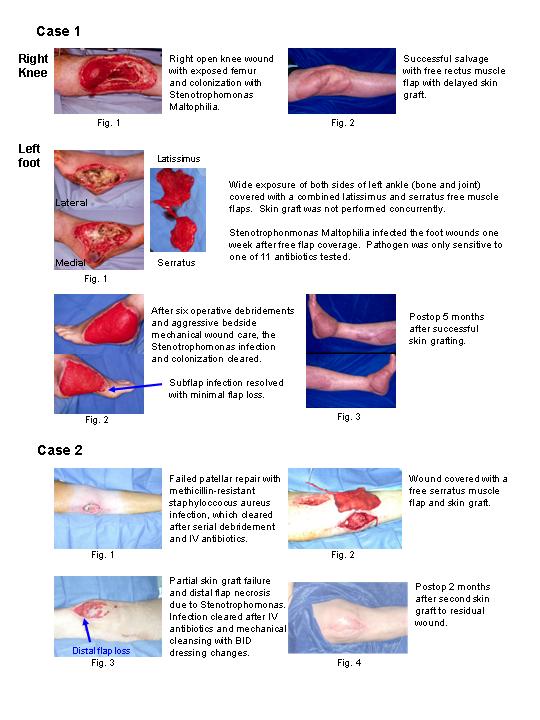

Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia(SM), previously known as Pseudomonas Maltophilia and then Xanthomonas Maltophilia, is an aerobic gram-negative bacillus. This organism is ubiquitous in the environment, but is not part of the normal skin or gastro-intestinal flora. It is found in soil, water, animals, and vegetation, and in the hospital it is found in sinks, ventilators, catheters, and needles. It has recently emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen in the immunocompromised patient population. There are multiple reports implicating SM as an opportunistic infection in cystic fibrosis, transplant recipients, neutropenic cancer patients, and patients on peritoneal dialysis. SM is resistant to a wide spectrum of antibiotics, and multiantibiotic therapy is considered a risk factor for the development of clinical SM infection. We describe two cases of infection of the free muscle flap used for coverage of lower extremity wounds. Muscle flaps are known for their reliability and resistance to infection, and they are employed to cover wounds even in presence of controlled wound sepsis. However, in these two cases, this pathogen was obviously resistant to the benefit of robust vascularity offered by the free muscle flap. From our experience of 130 free muscle flaps to the lower extremities managing various types of wound, including infected cases, we have had 6 recipient site infections. Two of these have been secondary to Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia infections.

One patient was caught in a hay baler and sustained multiple degloving and burn injuries to torso and both lower extremities. On his left lower extremity, he sustained a degloving injury across both the medial and lateral sides of his foot and ankle, which was reconstructed with a combined serratus-latissimus free muscle flap. Skin graft was staged and not performed at the time of the free flap. He developed a SM infection on his free flap 4 days later, which manifested as a persistent grayish mucopurulent film over the wound. He required one month of aggressive wound care with frequent bedside irrigation and debridements and 6 operative debridements before the wound was clinically cleared for skin grafting.

Our second case involved a non-insulin-dependent diabetic who fell during a truck-versus-pedestrian accident. He required an open right knee patellar repair, which became infected with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus infection. After debridement and resolution of MRSA infection, the open knee joint was covered with a serratus muscle flap with skin graft. Five days later the distal part of the skin graft became necrotic with slight dehiscence at tip of the muscle flap. Culture from the knee synovium at the time of the free flap coverage was positive for SM. Wound culture at the time of development of low-grade infection was again positive for SM. The physicians began twice per day thorough cleansing of the wound with frequent bedside debridement, and we were able to salvage the flap with minimal soft-tissue loss.

Insight from our experience indicates Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia may have a propensity to colonize and infect muscle flaps despite their bactericidal benefits. We recommend that when SM has been cultured from a free muscle flap, which is not healing as expected, the surgeon should not view the recovered bacteria as a common contaminant. Instead, it should be treated with aggressive wound care, IV antibiotics, and multiple debridement as indicated.